The concept of user-generated content (UGC) is not new. It first came to the attention of business analysts in the early 2000s, when it became apparent that companies like Facebook were becoming corporate behemoths not by churning out their own content, but by leveraging the value of content created by users. In a sense, Google was the first UGC business: its value is predicated entirely on managing our relationship with billions of other people’s internet pages.

For marketers today, however, UGC must be carefully managed. Customers can make or break a brand through reviews and social media. Yelp and TripAdvisor are good examples of collated and ranked UGC. And on Twitter and Facebook, brands are entirely at the mercy of popular opinion. Users are no longer passive recipients of brand image. Instead, they are co-contributors to the popular perception of brands, changing brand positions just by the way they talk about it online. And it’s not easy for companies to control what’s said about them.

Let’s look at some examples.

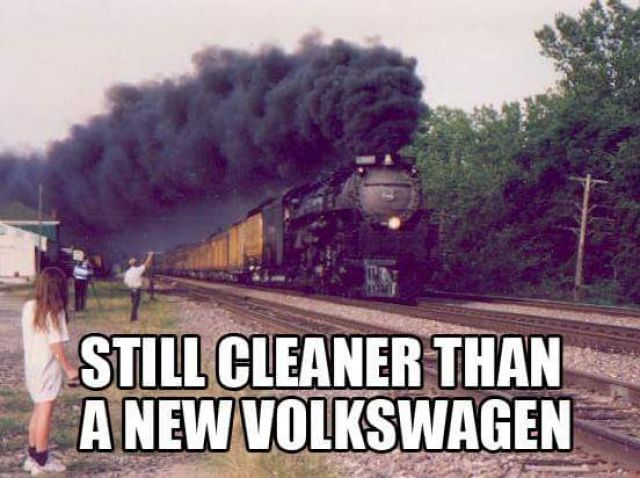

The recent scandal over Volkswagen and emission tests saw a massive backlash from social media users about emissions, spawning the damaging hashtags #dieselgate, #vwgate and #volkswagenscandal. By late September 2015, VW’s stock had dropped by 50% of its value. Negative social media and UGC certainly played a major part in the propagation of this PR nightmare.

But that’s a black-and-white example. What about the National Environment Research Council, who opened a Twitter competition to name their new ship? As I write, their new research vessel is on the brink of being named “Boaty McBoatface”. This is either an amusing (and not particularly costly) negative outcome, or one of the best pieces of marketing by a dowdy scientific institution in decades.

Or most interestingly, the furore about Stoke Gifford Parish Council’s decision to charge ParkRun participants £1 each, in order to pay for the upkeep of the park. This created a huge backlash on social media, including angry contributions from luminaries like Paula Radcliffe and Dame Kelly Holmes. But why should the parishioners of Stoke Gifford pay for non-residents to run through their park? It’s a great example of the fact that social media is not always right, and the instinctive outrage of the crowd is something brands really need to worry about.

It’s not all bad news though. Brands can work with audiences to create incredibly positive coverage, translating into hard profits. One of the most famous UGC campaigns was in 2009, run by Tourism Queensland. Titled ‘The best job in the world’, people were invited to submit videos of themselves describing why they should win a 6 month job ‘caretaking’ a paradise island. The campaign received over 35,000 applications from 200 countries and generated US$70m of global publicity for an initial investment of US$1m.

What these examples teach us is that UGC is a tiger which brands have no choice but to grab by the tail. It acts as an amplifier, both for good news and bad. As content production shifts, content co-creation becomes the new norm, and every business is along for the ride, whether they like it or not. UGC is growing inexorably, and it works because users believe it does. Prior to the 2015 General Election, for example, one third of 18-24 year olds polled by Ipsos Mori believed their voting decision would be influenced by social media.

The challenges are:

- How to filter new UGC information for relevance, reputation, and ultimately decision-making – to discern ‘the signal from the noise’.

- How to respond reliably and effectively to user-generated opinion, both positive and negative

- And how to react to the ugly truth: the crowd is not always right and not always well thought-through in its arguments.

This landscape is not immune to change. Facebook and Instagram have both been criticised recently for tweaking their newsfeed displays to either favour advertisers or encourage more participation. Facebook has seen sharing fall, and Twitter usage rates have, according to some analysts, plummeted dramatically. We can therefore guarantee that social media reputation management for brands is not going to be a colour-by-numbers affair: it demands constant attention.